For my Autumn project, I’m taking a look at the content of the Wood’s House collection of random books and nonsense as I compile an informal catalog. More fun with annotations ahead — this time with a bit of a dive into the history of education in the US!

The title page of Legends, Poems and Stories features a device with the following words on it: tout bien ou rien.[1] Roughly: do everything well or do nothing. The device in question represents a motto that was apparently long in use by the founder of the Houghton Mifflin Company, the book’s publisher. It’s a fine shot across the bow for a standard educational book (a literature reader for elementary school students), and sets the tone for a text that has a specific agenda, clearly laid out in the Foreword.

A pupil’s ability to enjoy good reading during his leisure hours presupposes training in appreciation of good literature that is within his comprehension during his hours in the classroom. There are, of course, any number of excellent poems, stories, and essays that may be selected for this training in appreciation. Whatever selection, however, is made should include stories with lively action or unusual situations that create sufficient suspense to guarantee that a pupil will not only wish to finish the story but will be greatly disappointed if he is interrupted in reading it. Such stories may very profitably carry a theme of patriotism, of growth of character, of the perception of the importance of commonplace events, or any other great truth with which young people should be made increasingly familiar in their formative years. [2]

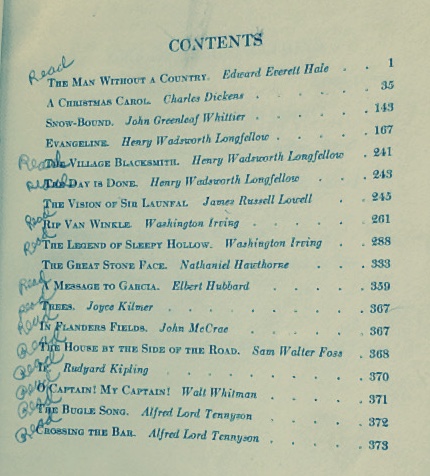

The table of contents reveals how the unnamed editors/compilers of the text chose to take the Foreword’s advice:

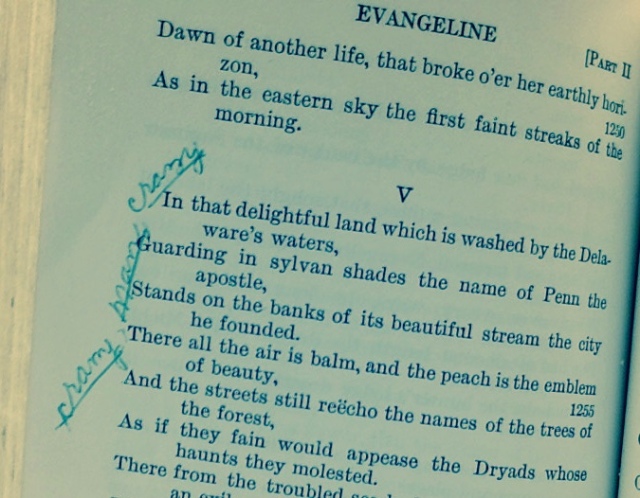

This particular book (according to markings inside, the property of Davis Creek District 36, No. 5 in 1942) went through several different hands, including those of someone named Patsy Einspahr who signed the inside of the front cover. It’s not clear whether Patsy or some other user marked off the selections in the text as read — someone obviously read Longfellow’s Evangeline, though, and that someone had an opinion about the experience:

Crazy, man, crazy

Apparently, this charming description of Pennsylvania seems to have been laying it on a bit thick for at least one young person being trained to appreciate literature.

Of course, not all of the annotations in Legends, Poems and Stories are critical commentaries of this sort. Bits of the text have names next to them, for example (perhaps students who have been assigned to read or present those bits). There are vocabulary notes on the blank back of an illustration in the middle of Hawthorne’s “The Great Stone Face,” listing helpful definitions for words like “titanic,” “purport,” “benign,” and “sylvan”; the author of these notes couldn’t quite figure out what “discerned” meant (having spelled it incorrectly), and said so. On another page in that same story, bafflingly, someone scrawled “Isn’t the story a story” in green pen in a water-damaged margin.

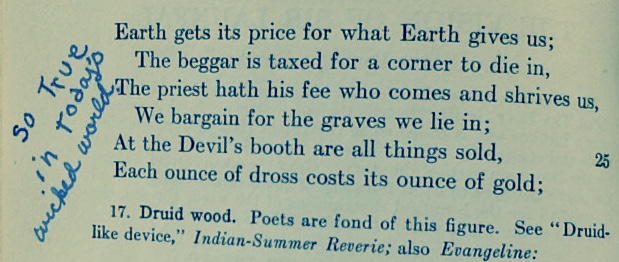

Some comments are trenchant observations about the times, such as this note on Lowell’s The Vision of Sir Launfal:

Apparently, not much has changed, although I don’t think I’ve heard a 7th or 8th Grader refer to the world as “wicked” recently (at least, not in this sense). Interestingly, the student who wrote that comment seems not to have had much to say about the rest of the stanza, which reads:

For a cap and bells our lives we pay,

Bubbles we buy with a whole soul’s tasking;

‘Tis heaven alone that is given away,

‘Tis only God may be had for the asking;

No price is set on the lavish summer;

June may be had by the poorest comer. [3]

For some reader, however, this slightly more optimistic bit had to be done by Monday (at least up to the line about God).

As is the case with most of the books in the Wood’s House collection, it’s impossible to tell exactly why Legends, Poems and Stories is here. It’s not a popular text in current circulation, although it does have some historical value. Harvard’s Graduate School of Education has a copy in its Gutman Special Collections, which covers “the history of schooling and learning in America,” but otherwise a cursory search for the book only turns up three Amazon sellers trying to move used copies for $30-$55. The Wood’s House copy is a little moldy, slightly water-damaged, and extensively annotated; someone even used the back leaf for Autographs (the only signature: Judy Veleba, whose very neat cursive handwriting is a slight improvement over Patsy’s hastier scrawl in the front of the book).

As is also the case with most of the Wood’s House books, though, Legends, Poems and Stories offers a fine excuse to sit down in a comfy chair and read a bit by the fire, a use which speaks well of how it realizes the aims of its compilers to encourage the enjoyment of good reading in one’s leisure time.

1. Legends, Poems and Stories Listed as Required Reading in the Seventh and Eighth Grades in Course of Study for Elementary Schools of Nebraska, published in 1936.

2. Legends, Poems and Stories, v.

3. Legends, Poems and Stories, 247.